An efficient battle against corruption was not possible without changes in political structures, but what we still don’t know is whether political changes are enough for great acts of anti-corruption.

Stevo Muk

When one says ‘corruption’, many things spring to mind for citizens of Montenegro. I would highlight the ‘Limenka’ case as it is the most obvious and unscrupulous one – a purchase arrangement between the government and the brother of the then-President of Parliament Milo Djukanovic. By the doings and undoings of multiple Ministers of Internal Affairs, Directors of Police, and other government officials, the state budget ended up many millions short, and the Brother was millions in gain.

The Special State Prosecution prolongued the investigation for almost a decade, under pressure by the opposition, the media, and the non-governmental sector; ultimately deciding that there was no criminal liability in this case. The damages to the state budget of nearly seven million euros (and just as much gain for the Prime Minister’s brother) remained, and no one had taken criminal, disciplinary, ethical, or political responsibility.

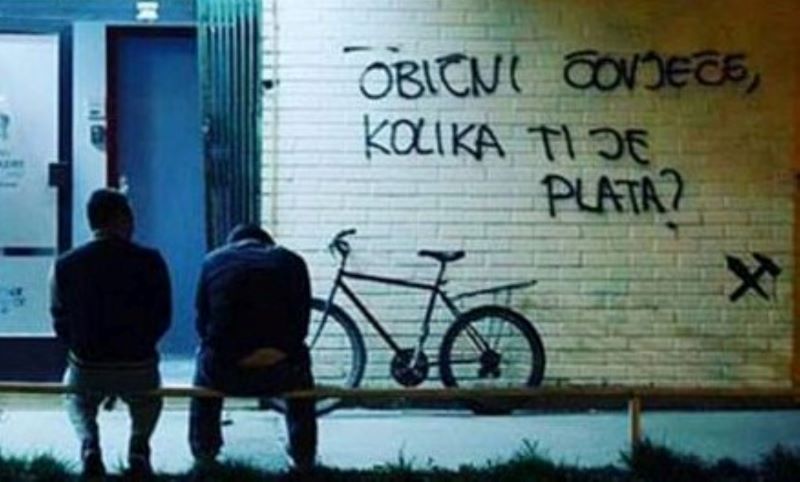

However, corruption in Montenegro is much more than a collection of great and well-known cases – these are only the tip of the iceberg. An acquaintance once told me that corruption in the City Council building is omnipresent, from the janitor to the mayor. The janitor resells the surplus of cleaning supplies, and the mayor takes his own cut in public tenders. Corruption has been ‘the only game in town’ for years and decades, and everyone seems to have found their place under the sun.

Montenegro is now choosing its first government not made up of the parties which had been in power in the previous decades. Our experience tells us that an efficient battle against corruption was not possible without changes in politics, but what we still don’t know is whether political changes, although a neccessary precondition, are enough for great acts of anti-corruption. That is why we pose a very valid question – ‘What are you planning to do about corruption and organised crime?’

Many promises have been made, and the expectations are high. Will they help prove what the critical opposition has been seeing and claiming for years, at what the ‘captured’ state has been turning a blind eye? A portion of the public is expecting one great sweeping action which will expose corruption and crime at the highest levels (meaning high government officers, and the tycoons of former government). There are suggestions of lustration, opening up files, questioning property ownership and origin. The regional experience, however, shows us that it is much easier said than done.

The real question is whether there will be established independent, professional, sustainable institutions in the foreseeable future – ones that can regulare the rule of law, regardless of future political changes. Because even if we do resolve issues of past corruption, what are we going to do about any future corruption? Other than the ‘sword’ of repression (police and prosecution), we will need mechanisms for prevention, which will build, empower and encourage integrity in public servants and public services at large.

We’ve seen tens of preventative mechanisms in the previous years, which remained nothing but dead letters. The political will, which has been lacking for a long time, will be at test again, faced with the ‘old regime’ and its obstructions. There is also the temptation to use at least some of the inherited mechanisms to preserve the new government. Corruption leads to the general weakening of the state and poverty in any circumastance, and during this time of serious economic crisis, Montenegro has an almost existential reason to put a stop to corruption once and for all. Along with building independent institutions, lead by real people, this society will need those who have given a great contribution to uncovering corruption – independent media, investigative journalists, and non-governmental organisations, as well as insiders (whistle blowers) – brave people from within the system itself.

Stevo Muk is president of the Executive Committee of the non-governmental organisation Institut alternativa, by the investigative center in Podgorica. He tackles investigations of public management, corruption, and rule of law.

Leave A Comment