A smidgen of time in history, yet for those who had witnessed the war, each day felt like a year. We are at peace, yet the war seems to still be in our minds. Continuing, peacefully, through the politicians’ combustible rhetoric. Coming to terms with the dark pages of our history is both heroic and human, and we ought to remember the wrongdoings, whoever their actors may have been.

Writen by: Zijad Sehic

Whenever there is an anniversary or a celebration of an important historical event, I am flooded with contradictory feelings. Along with sole facts, the essence of history, there is the tingling of emotions.

The city I live in is filled with history. This is where the First World War began. This month, we are celebrating the end of that war, it has been over a century. We are also marking 25 years of the Paris-Dayton Peace Agreement which ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. A smidgen of time in history, yet for those who witnessed the war, each day felt like a year. We are in peace, but the war seems to still be in our minds. Continuing, peacefully, through the politicians’ combustible rhetoric.What is left after the wars?

Sad memories, a count of those wounded and killed, devastated cultural, historical, religious, and civil premises. Then, the society begins to rise, renew what had been ruined. Monuments are built as permanent reminders of those events.

The most devastating ‘monument’ of the brutal past of our region is Mezarje in Potocari, by Srebrenica, and the death of over 8,000 Bosniaks – declared as a genocide by the International Court. Other places are also commemorating deaths. Each innocent victim deserves a monument.

Public conversation these days has been dominated by the erection of a monument to the Serb victims in Sarajevo. A marker of inhumane actions of soldiers over innocent civilians. This, of course, did not lack controversy, nor political connotations. It is pre-election season after all.

A colleague of mine, a historian, is resolved in his support of the monument. Coming to terms with the dark pages of our history is both heroic and human, and we ought to remember wrongdoings, whoever their actors may have been, in order to have the victims, even symbolically, become part of collective permanent memory.

In the end, no one can take our memories away. Each November, I think of the World War I Decree on Peace, in the French town of Compiègne, on 11.11.1918. Monuments remain.

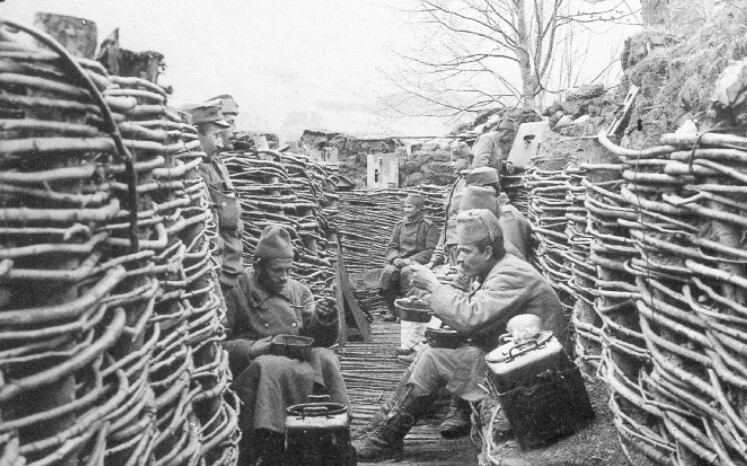

There is a great number of people from Bosnia and Herzegovina among the victims of the Great war, as it was a prominent war zone. 291,498 soldiers were recruited, or 16.2% of the population, with 8 infantry squads and battalions. They were also involved with the common forces of the Austro-Hungarian army, and other military operations on the Balkan Front.

Aside from the general poor conditions of the soldiers, and their troubles, 38 thousand soldiers from Bosnia have died, especially on the Italian Front. Simultaneously, the war brought military success and awards to distinguished soldiers and officers. 146 soldiers were awarded bravery medals; bosnia-herzegovinian infantry squads and battalions received 35,637 medals for bravery, and lieutenant Gojkomir Glogovac was decorated with the ‘Maria Theresia’, the title of a baron, and named the first Bosnian knight. Their contributions and bravery are marked by two memorial plaques and a monument.

One in the center of Graz, as a memory of the Monte Melleti Battle; Vienna’s Museum of military history has the memorial plaque of the 1st bosnian-herzegovinian squad, and in the midst of a military graveyard by Bovec in Slovenia, there is a monument with an etched royal shooter and a bosnian-herzegovinian soldier.

Monuments are silent witnesses of the past, of bravery, but also remind us of the hunger, thirst, cold, illness, all sorts of suffering… Is the artefact enough to mark the hurt in? Can it really stand for all the suffering brought by the war?! Can’t it at least be a warning to not have wars happen again? That our reality should be a smiling, happy individual, rather than the attempt to right past wrongs and consequences of the war. Then, we would not need international diplomacy to create our peace, and gather us at peace conferences. We would not wave goodbye to our dear friends and our own children, going to far-away countries in search for a better life. We would write and live a different, better, more beautiful history.

Professor Doctor Zijad Sehic is a tenured professor of the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Sarajevo, and president of the Doctoral Council at the History Department. He is a member of the Commission for history of South East Europe at the Viennese ‘Pro Oriente’ foundation.

Leave A Comment