It is said that homo sapiens is the only animal species that is able to imagine things that do not exist. Through a theatrical collaboration, the Mostar version of homo sapiens has shown that it is not only imaginative, but also can be a dignified signpost and an alternative to the pervasive state-political brothel.

Dragan Komadina

When I did the play “Let’s go for coffee” (translator note: original title includes local slang for coffee, an inversion of letters, ‘fee-co’) with my dear friends Robert Pehar and Sasa Orucevic seven years ago, I had no idea it would become a cult(ural) post-war Mostar brand, a play that can rightly be called one of the few true common cultural goods of both parts of the war-torn and post-war divided city. With the first reactions after the premiere, it had already become clear that something was wrong with the usual exchange of national and religious hatred in the media. Instead, one could read city news portals and see anonymous comments interspersed with expressions of overall enthusiasm and exceptional emotional understanding for the position of others in the war. I couldn’t hide my tears then or today. These anonymous people, mostly war veterans of opposing armies, and their views meant more to me than all the critical and theatrical remarks to which our play was not immune. Quite the opposite!

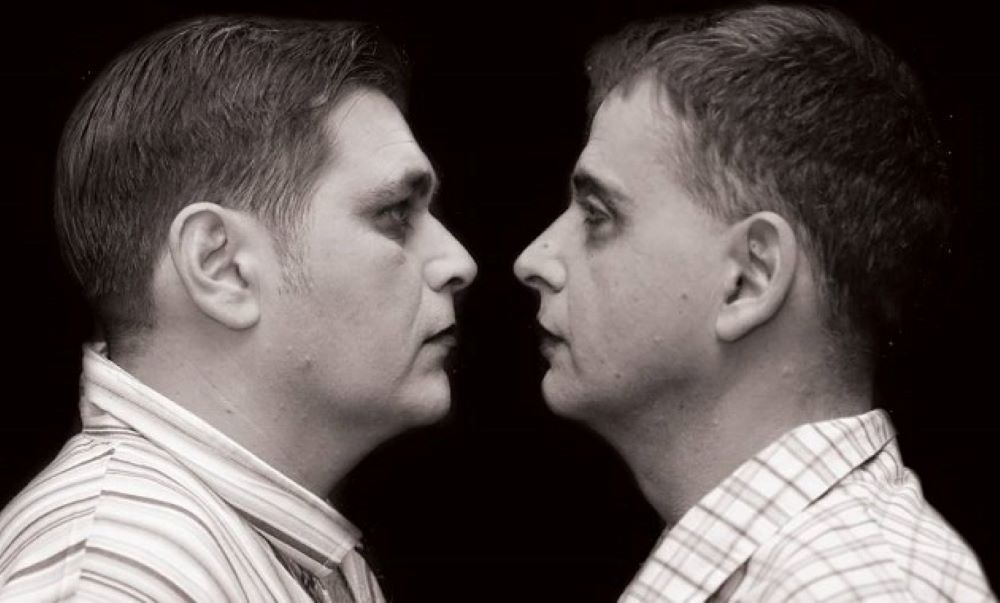

Confronting the audience with a heap of various prejudices that are systematically nurtured in all public spaces – from parliament to primary schools – and alongside theatrical applause also earn that much virtual praise, was an exceptional artistic and, above all, moral endeavour for all of us. Some have pointed out to us that the secret of the play’s success with the audiences – continued success, if I might add – lies in the dramaturgical scales with which we skillfully and evenly distributed the satirical sting to both sides, East and West, the HVO and the Army, Brazil and Argentina… They probably have a point. At least in part. You see, I am of the opinion that the real success of this play is not that it explicitly balanced with our ideologues and the symbolic war legacy of the still undecided federal political agony, but that it found its way to the heart of every individual in the audience. It brought our pre-war, war and post-war daily lives back to the level of individual recognition, in the way only theater and art can and should do. The audience understood the problems of two warriors who meet each other in the afterlife, here in Mostar, as their own and simply felt love for them. It may sound pretentious, but in its production and aesthetic unpretentiousness, as well as emotional and moral inclusiveness, ‘Let’s go for coffee’ has achieved significantly more than many international projects undertaken in these 27 years to build peace and trust in post-conflict societies.

I don’t know if I’m right. But I do know that in my career in theater, as a playwright, writer or director, I have never documented or criticized from a position of moral high-ground. I am one of those people I write about, one of them. But that doesn’t mean I still can’t and shouldn’t be ashamed of myself and of them. This play emerged from this moral and artistic microcosm, as a small intercultural miracle in which ex-soldiers and former enemies dispel the darkness of universal intolerance and lack of desire to understand and hear the Other with a theatrical torch.

Dragan Komadina, professor at the Department of Dramaturgy at the Academy of Performing Arts in Sarajevo and artistic advisor at the Croatian National Theater in Mostar

Leave A Comment