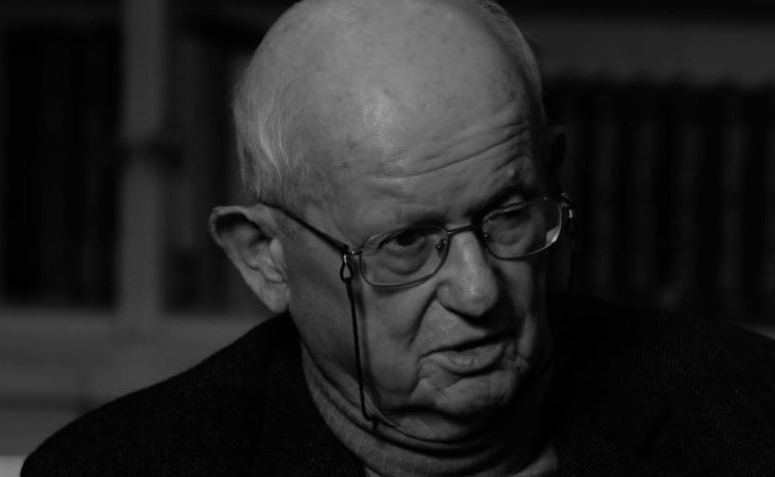

Kamhi’s passing almost brought the passing of Judaeo-Spanish, in which he sang Sephardic songs. Whenever I listen to them from now on, I will see his smiling face.

Edina Kamenica

I always trusted my own deepest intuition, which simply made me go to a lecture by the retired professor at the Academy of Music, David Kamhi, on the 25th of September last year.

Had I not gone, I’d be carrying a heavy weight on my chest today; as it would turn out, this was the last time I would see and speak to professor Kamhi in person. Like many in this storm, he was taken by the coronavirus pandemic. It took away a being who encapsulated not only family tradition, but the world views and cultural idioms of several civilisational circles.

He spoke spontaneously, about himself as a metaphor for the intellectual, erudite, polyglot… only when it appeared in a newspaper column it seemed to have carried additional weight for him. He called to thank me. And did he! I was almost embarrassed at the flood of compliments he directed at me.

Every phone conversation with the esteemed professor of violin and viola was precious, it was wonderful to hear him speak about his family history, the Sephards, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Europe, and the world; them being among the rare in the world with knowledge and evidence of their family origins in the 1st century AD, and the Museum in Jerusalem holding the information about mother Kamhiot and her eleven sons.

Their migration began in year 175, and has lasted for centuries, until their arrival in Sarajevo, where they were once again under threat in 1941. Professor Kamhi didn’t leave Sarajevo in the previous war either, when, as he would often point out, the Inter-Religious Council of Bosnia and Herzegovina was born – the trademark of inter-religious dialogue in the region.

My brother was born in October 1941, and my mother first hid in the Bauer Sanatorium; one day, the head of the institution openly told her that she could not stay there anymore. Our parents were friendly with Fahrija-hanum and beg Fadilpasic, who saved us. After the Sanatorium, we first went to Mjedenica, to stay with the Odobasic family, Sejfa and Marica. Soon, a ‘kulturbund’ came to stay, and asked my mum to go with him; everyone jumped at him – our hosts and the neighbours. All Muslims. Upon hearing about this, Fahrija-hanuma sent my mother a veil, and for me a fez. My mother kept telling me that if anyone asks, I am to say my name is Jawed, not David. I was five years old. And so we got on the train to Mostar – Kamhi told me, who, in addition to music, was also interested in the tradition of Bosnian Jews, and especially their relations with Muslims.

I found their roots in the Medina Charter of the Prophet Muhammad from the 7th century, where it is said, ‘to us our faith, and yours to you’. At the time, there were 70 Arab and 20 Jewish tribes on the Arabian Peninsula who, led by Tariq ibn Ziyad, conquered Endelus / Spain, Kamhi told me.

Kamhi’s passing almost brought the passing of Judaeo-Spanish. As fate would have it, he was the post-war Bosnian diplomat in Spain. He gifted King Juan Carlos a reprint of the Sarajevo Haggadah, a book brought to Sarajevo by Jews exiled from Spain.

Edina Kamenica, journalist, award-winning reporter, spent the majority of her professional career as a journalist in Oslobodjenje newspaper

Leave A Comment