Today’s Balkan cults of personality are based on the ubiquity of leaders in the controlled media. They also use the old methods of reshaping public space through new buildings and statues.

Filip Stojanovski

Seemingly paradoxically, in 2012, it was the regime of the declared anti-communist party VMRO-DPMNE that erected a new monument to Tito in the center of Skopje.

There was no public debate on that case. There is no public information on how it was paid. The Alliance of Tito’s Left Forces, one of their satellite parties of VMRO-DPMNE, whose main electorate was pensioners, boasted that the monument was their achievement.

The lack of unofficial reactions from the wider right-wing circles showed that there is a perception that Tito’s character still has a useful value for collecting political points, i.e. that the number of his admirers is far greater than the number of his haters.

From that perspective, it does not seem strange that Jordan Mijalkov, who previously held a number of positions in politics, economy and sports in SFRY, in his first interview for “Vecer” as the first Minister of Internal Affairs of the independent Republic of Macedonia in 1991, boasted that his sons had served in the JNA as military police officers in Tito’s Guard.

After 2006, one of those sons, Sasho Mijalkov, became the “almighty” head of the secret police within the right-wing populist regime led by his first cousin Nikola Gruevski.

It is also important to note that the authoritarian profile of the citizens was not built only in socialism. Most European countries cannot boast that even before World War II they had a high degree of democracy, measured by today’s standards.

Many of the inhabitants of the region were brought up in an authoritarian spirit, which meant worshiping an inviolable, almost superhuman leader who solves all problems. Such expectations in the interwar period 1918-1941 were built not only by the states ruled by fascist parties, but also by many others who oscillated between a fragile parliamentary democracy and a dictatorship, i.e. a monarchy.

Serbian analysts point out that the Kingdom of Yugoslavia as a state had invested in building the cult of personality of members of the Karadjordjevic dynasty, perhaps even more than the SFRY invested in building the cult of personality of Tito. Among other things, until 1941, this included naming the streets of Belgrade after other living members of the family, such as Prince Pavle and his wife Olga (nowadays, Despot Stevan Blvd. and George Washington St.).

Some of those practices continued. Both the king and Tito became the godfather of the youngest child from a large family, “donating” state support. Reports spread of cases in which an ordinary citizen had written a letter to the ruler and had drawn his benevolent attention with it. The modern form are directed meetings with the citizens in front of TV cameras, during which Gruevski and Vucic immediately called the competent civil servant on their mobile phone and “solved the problem”.

In 2014, “Global Voices” reported that supporters of the politicians Nikola Gruevski and Milorad Dodik demonstrated loyalty by tattooing their faces on their bodies, a practice that was also present in SFRY with the image of Tito.

Today’s Balkan cults of personality are based on the ubiquity of leaders in the controlled media. They also use the old methods of reshaping public space through new buildings and statues. But, unlike previous generations and Tito himself, they refrain from putting their image on sculptures, and use popular historical figures as a substitute.

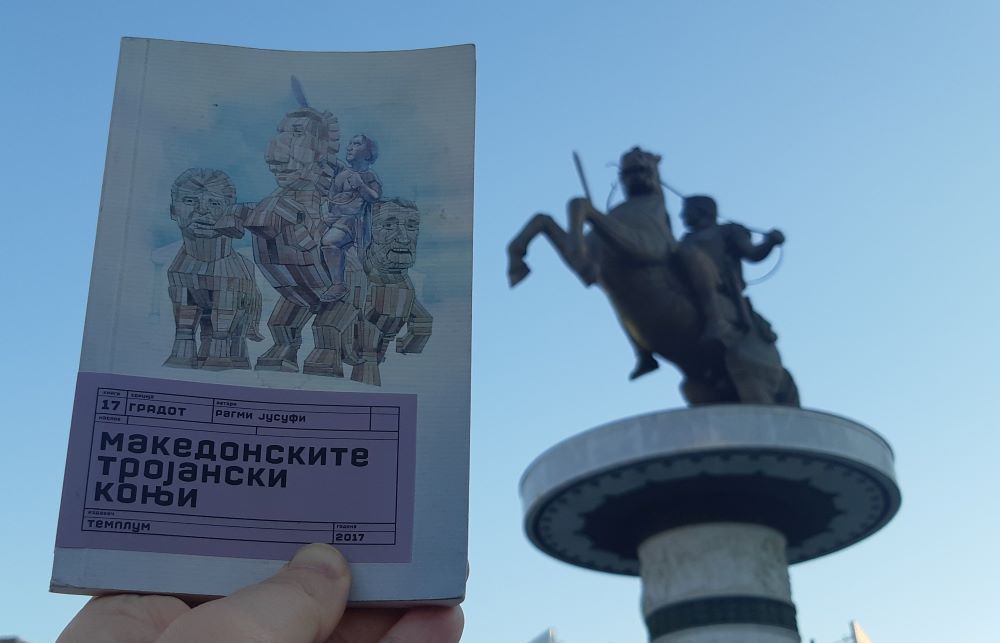

However, as Ragmi Jusufi points out in the book “Macedonian Trojan Horses” (Templum, 2017) everyone knows that monuments like the one of Alexander the Great are a surrogate for the client. This is also true for the new monument of Stefan Nemanja in Belgrade, and for the hundreds of smaller statues scattered throughout the Balkans over the last decade or two.

In the center of Skopje, for example, in addition to capital buildings that symbolized the power of the state, such as the Officers’ House and the Theater, the Karadjordjevic regime had erected equestrian statues of King Peter and Alexander in front of the Stone Bridge. The statues were demolished in 1941, and the buildings were damaged in the 1963 earthquake. However, all those buildings, together with similar statues of Macedonian revolutionaries, were erected again by Gruevski’s government with the “Skopje 2014” project, whose purpose, in addition to colossal laundering of state money, was to promote the power of Gruevski and his party.

One of the consequences is the “return” of the image of the city from the time when, according to the party ideologues themselves, the state was “colonizing”. Ironically, the situation in which a political force colonizes and exploits the institutions and the citizens is completely in line with the definition of “captive state”, a term used by the European Union for the anti-democratic system that ruled the Republic of North Macedonia until 2017.

Filip Stojanovski is an activist, ICT expert and blogger. He lives in Skopje and works for the “Metamorphosis” Foundation as a Partnership and Resource Development Director

[…] 2012, the right-wing populist regime in North Macedonia erected a new monument to Tito in the center of Skopje, indicating he had more admirers than haters within the electorate. Photo […]